This is a school assignment, from my junior year of undergrad. The course, Cartography, Territory, and Identity (taught by Bill Rankin), was fun and challenging for me. Although the course was taught without reference to the phrase “science and technology studies,” I see the critical study of maps from this course — as texts and technologies that had important cultural and geopolitical meanings but which could not be taken at face value (maps always tell only specific kind of truths) — as some of my first steps into STS. The perspectives from this course also led into my work with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project.

Also, pretty obvious, but this was originally written on a Word doc and I ported it over to markdown. I’m also doing this in April 2025, four and a half years after I wrote the thing. There are some inconsistencies I can’t be bothered to fix (like markdown in footnotes not working properly).

Introduction#🠑

My project explores the transition in mapping brought forth by the Japanese colonization of Korea. I begin with a set of precolonial Korean and Japanese maps to contextualize spatial knowledge before colonization, then discuss the Land Survey Ordinance of 1910 as a marker for the shift in maps as objects of modernization. Though the Ordinance proclaimed a relatively narrow goal of clarifying arable land ownership and collecting tax revenue, the Land Survey Bureau went further in establishing a discursive backbone for cultural products to emerge as well. These cultural aspects are especially visible in Japanese maps of the later colonial period, defined here as 1919-1945, and maps eventually became tools for creating consent from Koreans.

A substantial amount of scholarship has already discussed spatial knowledge in colonial Korea, mainly around how the Japanese land survey redefined property rights or gave rise to private landlords.1 These definitions of property are undoubtedly important to constructing space. However, as I argue for the rest of my paper, the Japanese project of spatial knowledge had a much broader scope than structuring economic relations. Spatial knowledge also served as an assimilationist tool. The products of spatial knowledge conveyed ideology specific to Japanese colonization and modernization, and served as a discursive bridge between overtly oppressive coercion and consent-generating cultural rule.

Historical and cartographic context#🠑

Maps were not introduced to Korea with Japanese colonization. Korea’s cartographic tradition had prevailed for several centuries before the annexation; the Kangnido, a Korean world map shown in Figure 1, is one such example as one of the oldest maps to come from East Asia and one of the most famous examples of Korean cartography.2 The Kangnido placed China at the center of its worldview, with Europe and Africa in irregular shapes near the left-hand side of the map. Japan is noticeably smaller than Korea, which is visible as a distinct but still connected part of the main continent of China. In addition to the Kangnido, maps from the early Joseon dynasty like the circular ch’onhado and the navy’s kwanbangdo maps similarly de-emphasized a rigid scale in favor of other purposes that were as diverse as translating folk tales or in giving conceptual sketches of coastal forts.3

Figure 1. The Kangnido World Map. From the National Institute for Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/km/print.do?levelId=km_015_0060_0020_0010&whereStr=

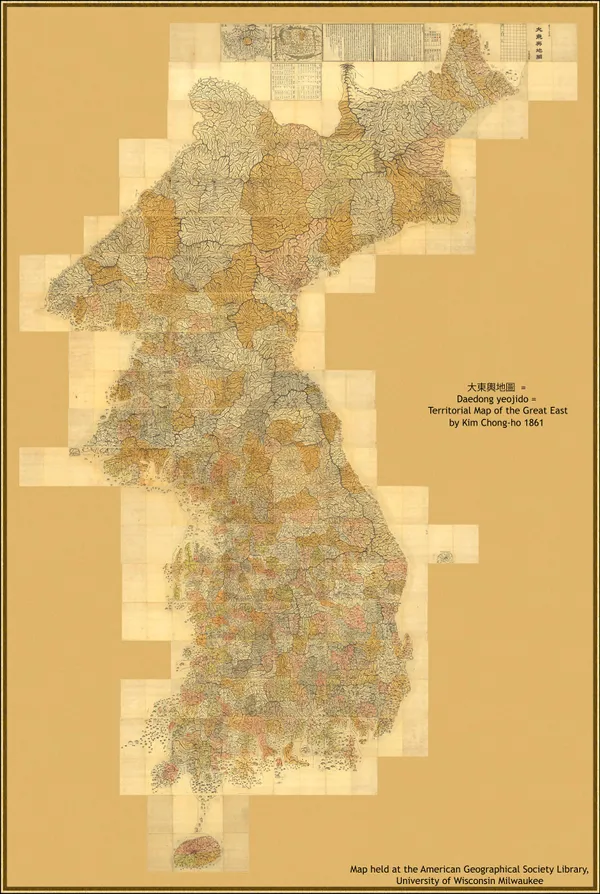

Most celebrated of Korean maps are the works of 19^th^ century cartographer Kim Chon-Ho, known foremost for his 1861 map of Korea titled “Detailed Map of the Great East” (Figure 2). At a scale of 1:162,000, and stretching 6.7 meters by 3.8 meters, this was the most detailed map of the peninsula to exist at the time of its publication. In the words of the Seoul Museum of History, for this level of detail, the map is “generally regarded as the greatest cartographic achievement before the modern era.”4 The details are specifically used to accentuate Korea’s national identity; while transportation routes and administrative divisions are shown, far more visible are Korea’s iconic mountain ranges and hills that cover nearly the entire country. The map also brings out Korea’s shape outside of its geographic context in a statement of Korea’s unique place in the world.

Figure 2. Chon-Ho Kim, “Territorial Map of the Great East 1861,” 1861, American Geographical Society Library Digital Map Collection, https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/829.

Representations of Korea shifted with political tensions in the late 19^th^ century. Twenty years after U.S. Commodore Perry’s expedition to East Asia forced Japan to open its borders, Japan in turn sent a gunboat to Korea in 1876 to the result of several small battles between the Japanese Un’yo ship and coastal Korean forts. After the Korean government realized it could not compete with superior firepower of the Japanese navy, the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1876 was signed and Korea opened its borders to Japanese merchants. Over several years, Japan developed an economic stake in Korea’s agricultural products that enabled Japan’s own growth, and eventually became politically embattled with China over economic dominance in Korean trade. At the same time, Korea suffered its own financial issues and issued successive land taxes for tenant farmers. These trends collided with the Donghak Peasant Rebellion of 1894 against excessive taxation from the Korean government, prompting the Korean government to ask China for military assistance. Japan, fearing that Chinese intervention would lead to de facto Chinese rule in Korea and an end to Korean trade with Japan, declared war on China and began the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894.5

These political maneuvers are reflected in cartographic representations, for example in an 1894 Japanese map shown in Figure 3. A coordinate system is shown in the map’s background, but the land features of the map do not follow the longitude-latitude system, and the shape of Korea is made diminutively thin. Korea’s provinces are noted through color in this period, marking Korea as a separate nation from China immediately before Japan entered war with China over its “older brother” relationship with Korea. Despite these noticeable administrative features, more salient in this map are the geological features of Korea’s mountains and rivers. Especially in contrast from later maps of the peninsula that are seen in the following sections, this representation of Korea is similar to that of Korean cartographers in emphasizing geological over man-made constructions, and in representing Korea as a distinct entity from its geographic neighbors. But the opposite message is conveyed because of the undersized Peninsula, where separation is not a declaration of strength and instead an indictment of weakness, arguing against Korea’s traditional relationship with China.

![Tokusaburo Wakabayashi, 'Shinsen Chosen Yochi Zenzu: Kan / Wakabayashi Tokusaburo. Saihan. Meiji 27 [1894]' (Wakabayashi Tokusaburo, 1894), University of Chicago LUNA.**](/images/korea-colonial-maps_figure_3.webp)

Figure 3. Tokusaburo Wakabayashi, “Shinsen Chosen Yochi Zenzu: Kan / Wakabayashi Tokusaburo. Saihan. Meiji 27 [1894]” (Wakabayashi Tokusaburo, 1894), University of Chicago LUNA.

Land surveys and a shift in spatial knowledge#🠑

After China was forced to end its protector-protectorate relationship with Korea in 1895, Korea entered a new period of independence. Knowing that Japan was encroaching onto the Korean Peninsula and that Korea’s independence might not last long, Emperor Gojong quickly set in motion the Gabo Reforms to resolve Korea’s financial and political issues and hopefully prevent colonization. Part of these changes was a new land tax for tenant farmers, who for hundreds of years had only paid rent to their immediate landlord. The tax was unsuccessful, especially in its earliest stages; which parcels of land were taxable to what extent was unclear given that land valuation was often made informally, regional differences in ownership structures made land tax laws ambiguous, and of course farmers across the peninsula objected to paying a second payment to the government they already saw as having failed them.

Korean Emperor Gojong began the Gwangmu land survey in 1898 as a uniform method to address such disputes. To some extent this was successful, providing authoritative documentation of the potential crop yield and current owner for each plot surveyed.6 But in other ways the Gwangmu survey was limited. In addition to valuation of arable land, the survey was also to include documentation of Korea’s forests and mountains with the intent of creating a new land management program based on a series of geological maps. The new Bureau of Land Management only ended up surveyed farmland due to financial issues from its very start. Measurements of the land were also imprecise, with the area of the paddy fields being defined as the area requiring one bushel of seed for rice, and the area of upland fields where rice was not planted being defined according to the area that could be plowed by one man and one ox in one day. The survey then ran out of funds completely in 1902, leaving many counties unsurveyed, no set of cadastral maps published, and leaving some scholars to question the last years of data collection.7

The project was finally limited by the trajectory of colonization during this time period. Japan sought again to deter rivals from Korea, which it was able to do after victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. Russia and Japan’s competing claims were now resolved in Japan’s favor, as all of Korea was recognized as under Japan’s “sphere of influence.” Japan then arranged the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905 two months after the War’s conclusion, forcing Korean Emperor Gojong to give up diplomatic sovereignty and making Korea a protectorate of Japan. Along with the terms of this treaty was the nullification of Emperor Gojong’s Gabo Reforms and thus the end of Korea’s modernization program. The Gwangmu land survey, which had already run out of funds at this point, ended in November 1905.

Thus, when Japan finally colonized Korea three years later and began its own project of spatial knowledge, it came after many years of gradual encroachment and after observing Korea struggle to implement its own system of land management. In the words of the new Japanese Governor-General of Korea:8

A complete land survey of Korea is of great importance in order to secure justice and equity in the levying of the land tax, and for accurately determining the cadastre of each region as well as protecting rights of ownership and thereby facilitating transactions of sale, purchase, or other transfers. Otherwise the productive power of land in the Peninsula can not be developed . The land tax in Korea is still levied on the old kyel system founded several hundred years ago. This system is not only incompatible with present economic and financial conditions, but also defective in itself, since it includes the so called Eun-kyel, or concealed kyels, which results in frequent attempts to evade the land tax.

Accordingly, the Governor-General issued Imperial Ordinance No. 361 two weeks after annexation, establishing the Land Survey Bureau and beginning the most comprehensive project of spatial knowledge on the Korean Peninsula up to that point. The Bureau avoided all of the financial and logistical limitations that it saw the Gwangmu Land Survey encounter, receiving enough funding to completely survey the land by its planned end date in 1918 and the Bureau itself remaining in operation until 1945. The survey was large in scope, with the National Archives of South Korea reporting the survey to have employed 12,388 workers (over 10% of all government workers), documented 19,107,520 lots of land, created 109,998 books for land registers, and most relevantly published 812,093 maps for recording the ownership, area, and value of each plot.9

The survey’s consequences were most immediately economic. Like the Korean Gwangmu Land Survey, these consequences were most explicitly related to an increase in tax revenue. As Kyung Moon Hwang notes in Rationalizing Korea, land tax revenue rose 17% after the completion of the survey, and the total land area subject to taxation rose 53%.10 Unlike the Gwangmu Survey, the Japanese Land Survey Bureau also abolished the default ownership of all land by the Korean Emperor. It also allowed the confiscation of land where ownership could not be proved, a common scenario for farmers who had made ownership agreements informally. These, along with the official valuation of every plot of land, made much more land available for sale to private investors like the Oriental Development Company and the Korea Development Bank. When an unexpectedly poor harvest in 1918 Japan led to a sudden rise in Japanese grain prices, the Oriental Development Company used these massive land holdings to export more than half of all rice produced in Korea to Japan.11 For Korean subjects, land kept over generations instead was lost, and farmers often moved towards urban centers and sought jobs in Japanese-owned factories.

The Japanese land survey was only able to bring these changes about because it began with a redefinition of the logic behind land valuation, which the Gwangmu Land Survey did not attempt. The precolonial methods of valuing land did not sit well with the Governor-General, and in a report planning the cadastral survey, the administration complained that “these crude measures vary according to different districts of the country, and so to know the exact area of the land is almost impossible… [the ownership certification] was so simple and crude that fraud or spoilation was a common practice in the sale and mortgage of lands.”12 In response, the cadastral survey set in place a fifty-item scale to value land based on soil quality and prior crop productions, applied uniformly to every part of the colony. Other measures that were determined informally in the precolonial era, like ownership structures (some regions had “intermediate” landlords between nobles and peasants, while others did not), were similarly unified by the Japanese cadastral survey.

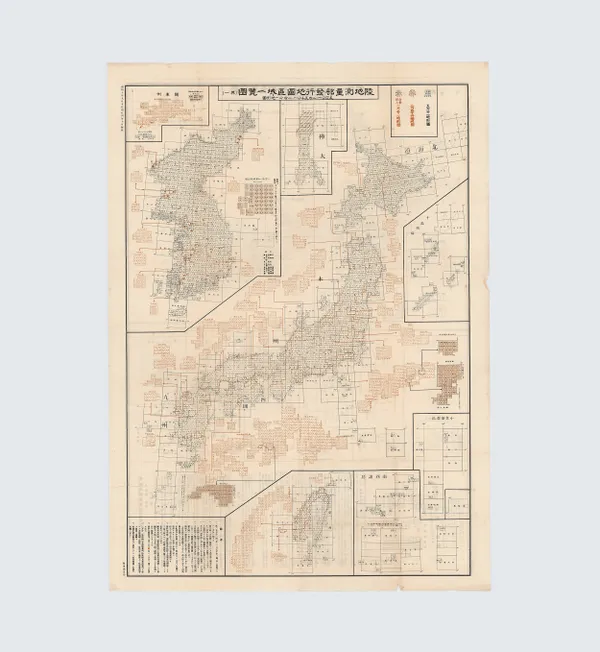

Figure 4. Government-General of Korea, “육지측량부발행지도구역일람표 // List of Map Areas Issued by the Land Survey Department,” 1935. Seoul Museum of History.

But the Bureau’s logic of redefining spatial knowledge was not limited to simply clarifying value or ownership, as the official motivation for the survey quoted above would suggest. Spatial knowledge was also useful as a tool of assimilation, bringing the heterogenous ways of knowing land in Korea into a single set of Japanese-defined rules. This goal is evident in the project’s first stage of triangulation that came even before valuing any land itself. Japan first used the island of Tsushima to link the southernmost part of Korea and the easternmost part of Japan, enabling the integration of Korea into the international coordinate system that Japan used. The relatively small island of Tsushima in this way became what David Fedman calls the “cartographic linchpin” of the Japan-Korea colonial relationship.13 As shown in Figure 4, the coordinate system as a grid also allowed Japan to represent itself and its colonies together as the Japanese Empire. On the macro-scale, Japan and its colonies of Korea, Hokkaido, Taiwan, and Sakhalin are given the common unit of the grid cell that portray them as parts of the unified Japanese empire, where Japan occupies the commanding center. Conversely, the grid cell and the orange sub-grids for urban centers emphasize the granularity of Japan’s knowledge; as opposed to being only a high-level argument of unified states, the project of the Land Survey Bureau penetrates and defines every corner of its empire. Finally, the coordinate system not only served as a means to assimilate Korea into the logic of Japan, but also bring the former “Hermit Kingdom” into the modern world.

The grid also serves to overwrite the existing divisions of the Korean peninsula, such as the provinces in Kim Chon-Ho’s map seen above. While Korea’s former administrative divisions were not replaced with the grid completely during Japanese rule, the Land Survey Bureau even redefined these to follow a unified set of rules. After observing some villages were bigger than districts and that districts could overlap in area, the Bureau concluded that the administrative divisions of Korea were in a “confused state” and planned since the year of annexation to rid the colony of these apparent contradictions.14

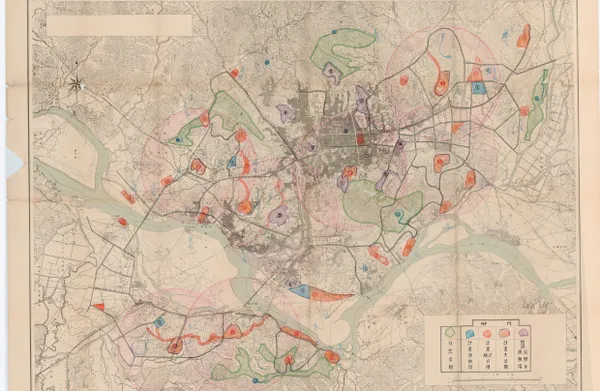

This new spatial logic as a tool of rule can also be seen on smaller scales, for example in two 1:10,000 maps of the inner portion of Seoul. This series of maps is currently known as the largest and most detailed of the city to emerge during occupation. This map series was important enough for the Land Survey Bureau to publish four editions from 1918 to 1936 and conduct several smaller surveys to account for new streets and the movement of government offices. In other words, where the land valuation stage of the cadastral survey inscribed a vast amount of spatial knowledge into hundreds of thousands of relatively simple maps for daily interchangeable use, this project instead did the opposite of pouring much detail into four versions of a single map.

Figure 5. Land Survey Bureau Map of Seoul, with plans for parks, playgrounds, and stadiums, 1920. Seoul Museum of History.

At face value, this is at odds with the Bureau’s original mandate, for no arable land existed in Seoul and the map’s scale would have made it difficult to use for tax purposes. Instead, this map is reflective and even productive of the Japanese project of modernization more broadly. The map emphasizes the city’s streets with the inset on the map, a traffic schematic of the main city center. The items detailed in the map’s legend are not markers of natural formations, but projects of Japanese rule including the post office, the hospital, the shrine, and even the points used in the land survey’s triangulation of the area. In addition to representing these developments, the map’s annotations show that this map series served as a tool to build future parks and stadiums and develop the city.

The March First Movement of 1919 and maps as propaganda#🠑

Koreans fought back against Japanese colonialism. Inspired by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points at the conclusion of World War I, and especially swayed by Wilson’s apparent belief in the “free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims,” Korean students studying in Japan gathered to write the Korean Declaration of Independence in 1919. The signees demanded an end to discrimination against Koreans in government employment and education, land appropriation by the Japanese, the imposition of taxes that Koreans could not pay, and the usage of cheap Korean labor by Japanese capitalists. These demands were read aloud in Seoul on March 1^st^, 1919, sparking a nationwide protest movement began that has become canonized today as the March First Movement. Over two million Koreans participated in more than 1,500 demonstrations across the peninsula. These incited a new age of resistance, leading to the Battle of Bongo-dong and the Battle of Cheongsanri in 1920 between Korean guerilla fighters and the Japanese Army in Manchuria. It also marked a rise in labor activism; as historian Carter Eckert notes in Offspring of Empire, although only 6 labor disputes occurred in 1912, around 170 strikes occurred yearly by 1930.15

In many ways the movement failed. Police and military repression shut down protests violently, resulted in the death of 7,509 Koreans according to historian Park Eun-Sik. The Japanese government did not agree to any of the demands outlined in the Declaration of Independence, and Carter Eckert argues that Japan’s response to labor protests after the Movement was “utter indifference to the root cause of the disturbance… [, and Japan] did nothing really significant to ameliorate the harsh conditions of colonial labor in Korea.”16 Woodrow Wilson denied any notion of support to the Korean independence movement, and support from former allies like China and Russia was limited given that these countries were facing their own internal political issues. Korea was not able to attain independence until Japan was forced to relinquish its empire after World War II.

Instead of granting freedom to Koreans, Japan responded with a new era of cultural rule that included public-oriented propaganda maps. Japan realized that overtly physical rule would only result in more unrest, and that rule instead had to actively create consent from Koreans as well. These efforts could not simply be symbolic gestures at public events, and instead had to permeate every part of Korean life. As one Japanese official argued for assimilation, “even if you cover up something that smells foul, the stench will someday seep out.”17 The “stench” of dissent was therefore attacked with cultural products like postcards, posters, highly publicized exhibitions, the careful introduction and censorship of Korean-language newspapers, and most relevantly for this project, a new set of public-oriented maps.18 Compared to the technical maps seen in Figures 5a and 5b, which provided an internal cartographic grammar for the project of land management, this new set of maps included pictures, more vivid coloring, and text. These made them visible and recognizable products of Japanese-led modernization.

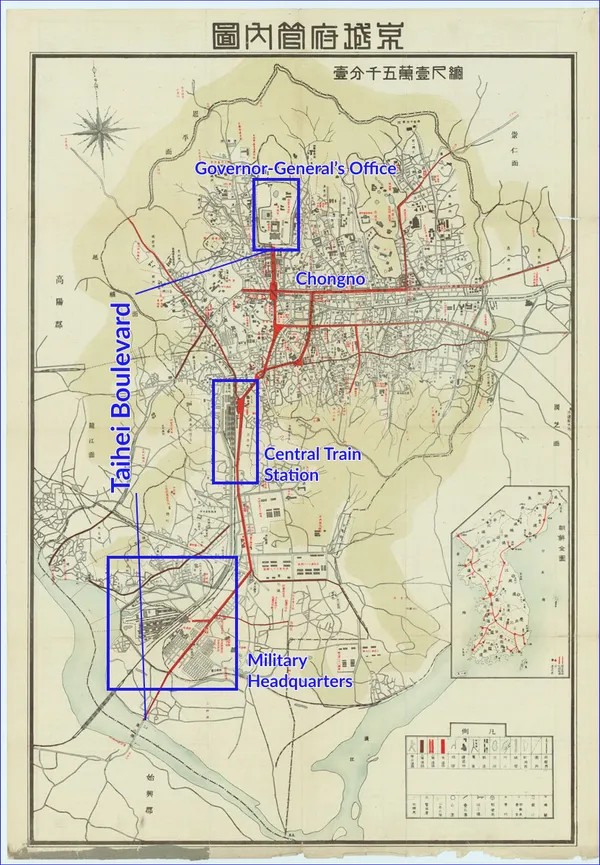

One example of this propaganda function can be seen in a 1926 map of Taihei Boulevard in Seoul. After the completion Taihei Boulevard’s renovation in 1926, the street became the main throughfare of Seoul. At its northernmost point was the Governor-General’s Office, which was built near the beginning of the colonial period on the grounds of the former Korean Emperor’s Kyongbok Palace. A short distance below, where Taihei Boulevard met Seoul’s main east-west street called Chongno, was a giant Japanese-built plaza that formed the major shopping and business hub of Seoul. Near the edge of the city, Taihei Boulevard meets the Central Train Station that was completed in 1925. The train station served as an economic link for resources from Korea’s countryside to Seoul and then to Japanese consumers via the nearby Han River, a function emphasized by the Chosen Railway system shown in the inset of the map. The Japanese military headquarters can be seen outside of the city and at the southernmost point of Taihei Boulevard.

Figure 6. Map of Gyeongseong (Seoul), publisher unknown, annotations my own. 1927. https://archives.seoul.go.kr/exhibition/yongsan/2/5.

This map conveys a story by selectively bringing forth detail, a contrast from the Figure 6’s massive size and overflowing detail used to represent the extent of Japan’s knowledge in Seoul. This allows the map to make a metaphorical argument of the city as a body: just as William Bowie called the Japanese cadastral survey the “backbone” of its economic project, Taihei Boulevard similarly serves as the spine for the modernized organism Seoul has become. The metaphorical “head” of Seoul’s body is the administrative center of the Governor-General’s Office that directs every development project in Korea, below it being the biggest shopping plaza that serves as the “heart” of everyday life for Korean subjects. These are made into one structure by Taihei Boulevard, sixty meters in width and thus structurally formidable as if a spine of a living body,19 and finally connected by the red “arteries” of secondary street projects to each corner of the city.

The north-south orientation of the map layers this argument with another metaphor justifying colonial rule. Fundamental to the city according to Japan is the political order seized and maintained through military force, and the city grows from this structure at its very bottom. But the military headquarters is on the outskirts of the city and thus less proximate to the Korean subject’s imagination compared to the economic functions of the Central Train Station located a short distance above it. The Korean subject’s life in Seoul, in the matrix of streets in the middle of the map, is thus built over foundations of Japanese economic and military order, no matter how conveniently out of sight from daily life these forces might be. From this position in the city, the Korean subject can look “upwards” geographically to receive the orders of the Governor-General’s Office, which has taken the physical and functional place of the Korean Emperor. According to the map, the city now operates on this new social order, built on top of force that is necessary for the peaceful modernized life of the Korean subject.

These developments in the city were undoubtedly physical, for Japan invested millions of yen into building the aforementioned physical structures. But the map is no less significant, for it connected all of these parts of the city in a cohesive set of narratives justifying colonial rule, and then presented this meaning to the Korean subject. The map thus served as a bridge from material to cultural rule, translating Japanese physical developments into culturally recognizable images. This link between materiality and discourse was precisely what was needed for the Empire after years of physical rule were unable to prevent rebellion.

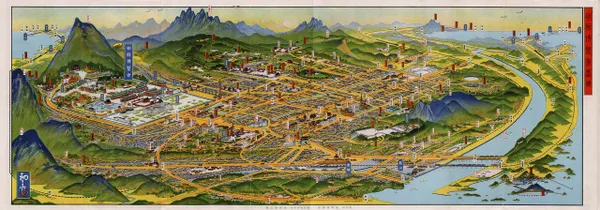

A third map of Seoul from the 1929 Seoul Exhibition is even more explicit in publicizing Japanese development in the city and nation. The 1929 Seoul Exposition was the third Japanese-installed exposition held in Korea, the former two being in 1909 and 1915 and also in Seoul. Japan poured millions of yen into these projects to attract both Japanese and Korean tourists, building new museum-like compounds to showcase technological advancements. The 1929 Exhibition took place inside the Kyongbok Palace complex in front of the Governor-General’s Office. Upon entering the exposition grounds, Koreans first saw twenty or so maps like those in Figure 7, three-dimensional images that display the city with vibrant colors as if a miniature exposition themselves. Visible in the below example is the exposition itself on the left, framed by the grid of the city brightly lit by Japanese-installed streetlights. The Chosun Shrine, the Korea Shrine, and Taihei Boulevard are visible in this map as well. Strange here is that the exterior of the city is greatly distorted, such that the cities of Wonsan, Geumgangsan, Daegu, Gyeongju, and Busan are all visible on the map but made much smaller than Seoul. The bird’s-eye view here recognizes Seoul for Korea as a whole in a cartographic metonymy aided by the generous amount of distortion.

Figure 7. A bird’s eye view, drawing the empire’s ambition. Hatsusaburo Yoshida, for the Seoul Exhibition of 1929. http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/815474.html

As the viewer moves past the maps of Seoul, they are surrounded by exhibition halls that are reconstructed models of the Kyongbok Palace’s demolished buildings. Already fifteen years have passed since the partial demolition of Kyongbok Palace for the construction of the Governor-General’s Office, and the models are thus for expo-goers as a trip to the past. This is only momentary; as the viewer continues past the “Korean”-style buildings, they encounter next the Metropolitan, Civil Engineering, Architecture, and Communications Halls, all in a “Western” Neoclassical style of architecture with high domes and decorative pillars. These were followed by the last set of buildings, a modernist set of buildings with overlapping curves and geometric shapes.20

This journey through the exposition is framed by the initial maps’ presentation of a modernized Seoul as a substitute for the whole of Korea. The trip through the exposition itself also serves as a trip through time, beginning with representations of Korea’s past and ending with modernist architecture connoting future developments for the city. Seoul residents who explore the exhibition thus experience a cartographic and architectural argument for the city as a space of progress: Japanese-led modernization in the city must be had in order to move the whole country forward.

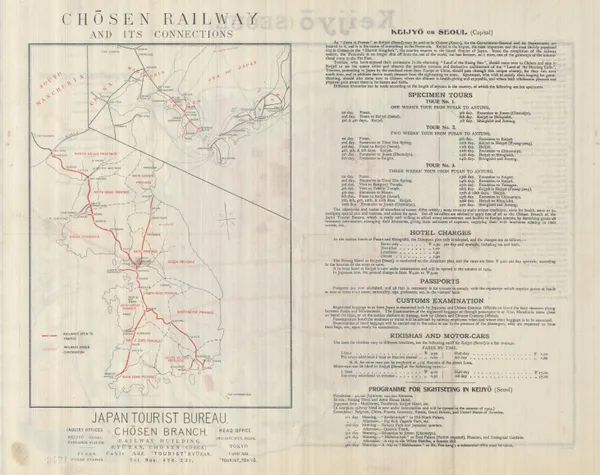

The specific maps of Seoul were a key part of representing Korea broadly, especially to gain recognition of its modernization project by international observers. In an English-language tourist brochure, the Tourist Bureau of Japan enticed travelers to visit Seoul with a map of the Korean peninsula, stating that “as ‘Paris is France’ so Keijyo (Seoul) may be said to be Chosen (Korea), for the Government-General and its Departments are located in it, and it is the centre of everything in the Peninsula.” Considering that Seoul was much smaller than Paris, and also that Korea was less concentrated in urban centers as France was, it is evident that the Tourist Bureau stretches to compare Korea to modern centers.

Figure 8. Chosen Railway and its connections. Japanese Tourist Bureau, 1913. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2018/05/maps-of-seoul-south-korea-under-japanese-occupation/

But Korea, even according to this map, is not a modern symbol exactly like France. It is instead a colony under development, newly connected to the world thanks to the work of Japan. Recasting Korea’s “premodern” history is essential to this narrative, forming a backdrop against which the Governor-General’s developments can be emphasized and ultimately Japan itself be valued. In this effort, Korea is called a former “Hermit Kingdom” where tourists can now go to “see the quaint attire and observe the peculiar customs and distinctive architecture of the ‘Land of the Morning Calm’“. Similarly, although the Korean name of Seoul is present for the nation’s capital, it comes after or as a parenthetical to the Japanese name of Keijyo while all other names for locations in Korea are shown only in Japanese. Korea’s national character is further diminutively displayed through the brochure’s advertised touring options: even as tourists can “derive much pleasure from the sightseeing” in Korea, the tours are ultimately routes either for tourists “proceeding to Japan by the overland route from Europe” or for tourists who have already “enjoyed their excursions in the charming ‘Land of the Rising Sun’” and are making their way home. Each tour stretches from Fusan, Korea’s closest port city to Japan, to Antung, on the border between China and Korea. Korea exists as an intermediary land between Japan and China, a tourist attraction that is denied its own equal footing among modern nation-states even as Japan proclaims Korea is entering the age of modernity.

The Chosen railway is the centerpiece of this argument on the transitions of tourists to Japan and of Korea to modernity. The Tourist Bureau declares that “since the completion of the railway system, the Peninsula is no longer shut off from the rest of the world, but has become, as it were, one of the gateways of the International route to the Far East.” On the map itself, the railway is made distinctly red against the black-and-beige background, marking it as one of the most interesting parts of the nation and one that facilitates connections with other nations. As in the map emphasizing Taihei Boulevard in Seoul, the Chosen Railway through cartography is represented as a development of Korea’s interior through connections with its exterior: the Japanese Empire and world at large.

In sum and beyond#🠑

Maps in colonial Korea provided a language through which Japanese rulers could make physical developments recognizable as an integrated project of modernization. In the land survey, these maps both reflected and were productive of modernization, by assimilating Korea into the spatial logic of Japan and enabling further economic and cultural development on the Peninsula. Japanese maps also served ideological roles after the completion of the cadastral survey, as a cultural product to represent material developments. These were especially useful following the March First Movement, after which Japan realized its physical rule through military occupation could not function without generating consent from Korean subjects.

These methods of rule did not disappear with “liberation” in 1945. As with all empires, the colonial project of management lived on. The U.S. Army Mapping Service after World War II used topographic data from the Japanese Land Survey Bureau in their own maps, and valuation data from the land survey was used for property assessment even towards the end of the century.21 Taihei Boulevard lives on today under the name of Taepyeongno, one of the uncountably many structures built during the colonial period that blend in seamlessly with Korea’s more recent developments. While this paper has attempted to show how colonial rulers can maintain order through maps and the discursive structure underlying them, further questioning is needed to understand exactly how these structures affect our lives today.

- Edwin H. Gragert, _Landownership Under Colonial Rule: Korea's Japanese Experience, 1900-1935_ (University of Hawaii Press, 1994); Young-Ho Lee, "Land Reform and Colonial Land Legislation in Korea, 1894-1910," in _Colonial Administration and Land Reform in East Asia_, ed. Sui-Wai Cheung (Routledge, 2017), 166--80; Gi-Wook Shin and Michael Edson Robinson, _Colonial Modernity in Korea_ (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1999). ↩

- Kenneth R. Robinson, "Gavin Menzies, 1421, and the Ryūkoku Kangnido World Map," _Ming Studies_ 2010, no. 61 (April 1, 2010): 56--70, https://doi.org/10.1179/014703710X12772211565945. ↩

- Gari Ledyard, "Cartography in Korea," in _History of Cartography_, by David Woodward and John Brian Harley, vol. 2, 2 (University of Chicago Press, 1994), https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V2_B2/Volume2_Book2.html; Han Young-Woo et al., _The Artistry of Early Korean Cartography_ (University of Hawaii Press, 2008); John Rennie Short, _Korea: A Cartographic History_ (University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩

- "Detailed Map of Korea (Daedongnyeojido), Woodblock" NATIONAL MUSEUM OF KOREA, accessed December 18, 2020, https%3A%2F%2Fwww.museum.go.kr%2Fsite%2Feng%2Frelic%2Frepresent%2Fview%3FrelicId%3D2577. ↩

- Gi-Wook Shin, _Peasant Protest and Social Change in Colonial Korea_ (University of Washington Press, 2014); Shin and Robinson, _Colonial Modernity in Korea_. ↩

- Lee, "Land Reform and Colonial Land Legislation in Korea, 1894-1910." Lee also notes that there are many discrepancies in the ownership documentation, as the Korean government was only interested in securing taxes for a plot instead of knowing the true owner. Naming systems also differed across region, a practice which the government did not attempt to standardize. ↩

- Kyung Moon Hwang, _Rationalizing Korea: The Rise of the Modern State, 1894--1945_ (Univ of California Press, 2015), 38--50. ↩

- Government-General of Chosen, _Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Chosen (Korea)._ (Keijo (Seoul): Government-General of Chosen, 1910), 40, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006782593. ↩

- "우리역사넷," accessed December 18, 2020, http://contents.history.go.kr/front/hm/view.do?treeId=010702&tabId=03&levelId=hm_131_0060. ↩

- Hwang, _Rationalizing Korea_, 43. ↩

- Hwang, 63. ↩

- Government-General of Chosen, _Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Chosen (Korea)._, 1910, 40. ↩

- David A. Fedman, "Japanese Colonial Cartography: Maps, Mapmaking, and the Land Survey in Colonial Korea," _The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus_ 10, no. 52 (December 24, 2012), https://apjjf.org/2012/10/52/David-A.-Fedman/3876/article.html. ↩

- Government-General of Chosen, _Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Chosen (Korea)._ (Keijo (Seoul): Government-General of Chosen, 1912), 22, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006782593. ↩

- Carter J. Eckert, _Offspring of Empire: The Koch'ang Kims and the Colonial Origins of Korean Capitalism, 1876-1945_ (University of Washington Press, 2014), 203. ↩

- Eckert, 203. ↩

- Mark E. Caprio, _Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945_ (University of Washington Press, 2011), 115. ↩

- Hyung Il Pai, "Staging 'Koreana' for the Tourist Gaze: Imperialist Nostalgia and the Circulation of Picture Postcards," _History of Photography_ 37, no. 3 (August 1, 2013): 301--11, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2013.807695; Todd A. Henry, _Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910--1945_ (Univ of California Press, 2016); Caprio, _Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945_; Hong Kal, _Aesthetic Constructions of Korean Nationalism: Spectacle, Politics and History_ (Routledge, 2011). Interestingly, the Dong-a Ilbo and the Chosun Ilbo, two of Korea's three most popular daily newspapers today, were introduced in 1920 as part of these changes. ↩

- As a reference, Broadway above 59^th^ Street in Manhattan is 45 meters wide, and the average avenue in Manhattan is 100 feet wide (about 30 meters). Taihei Boulevard was really wide. ↩

- Henry, _Assimilating Seoul_, 118. ↩

- Hwang, _Rationalizing Korea_, 43; "AMS L752 Topographic Maps - Korea - DMZ Era," accessed December 18, 2020, https://www.koreanwar.org/html/korean-war-topo-maps-l752.html. ↩